I had other plans for this week, but after two (count ‘em TWO) surgeries and a trip to the ER last week, I changed my mind. I appreciated the laugh at the time—I’d already spent way too much time crying—but it’s the kind of hollow laugh you make when you’re trying to pretend the world isn’t screwed up.

You know, the laugh I specialize in.

Violet Baudelaire: What’s the fastest way out of this hospital?

Babs: There is no fast way. First, you have to file the release papers in quadruplicate. And then those papers have to be authorized.

Violet Baudelaire: Is there a way out of here where I don’t have to fill out any paperwork?

Babs: You can die.

~A Series of Unfortunate Events: The Hostile Hospital (Part 2)

It never ceases to amaze me the amount of paperwork the medical community generates. We’ve entered the 21st century, where everything is digitized and stored on clouds and server farms, retrievable regardless of how many miles separate your primary care from your specialist from your urgent care. We’ve taught robots to read scans in seconds. Yet every visit is marked by the same request to complete the same series of questions.

As if the answers aren’t logged in a data file—hundreds of data files—already.

Who are you? Did you change the name registered to the birthdate logged in the system? Perhaps select a new birthdate more in line with your astrological leanings? Decide your legal name no longer suited you?

Are you single? Married? Divorced? Caught in a complicated love triangle with a high school sweetheart and your ex-boss?

Have you packed up and moved since you set foot in a medical facility less than 24 hours ago, uprooting your family and displacing them to a new state because you spontaneously enrolled in a witness protection program?

Do you still like your emergency contact, or would you like to shake things up and select a random person no one will actually reach out to even if you happen to go into cardiac arrest? (Incidentally, the system is not interested in mistakes. Do you think you know better than a medical file how to spell your father’s name?)

Over and over, they shove the forms into your hands, insisting you complete the answers. Again. And again. A constant test to confirm who you are. (As if anyone else wants to claim your medical history) Complete with multiple buttons and checkboxes insisting you certify that your answers are accurate and complete to the best of your ability because they are a matter of permanent record.

Which will disappear into the mysterious aether the second you hit “Submit.”

Doctors never have anything in their hands when they approach in the ER. No tablet containing the record you spent 20-damn minutes updating (or even the records sitting on that stupid cloud where your encyclopedic medical history resides), no notepad for writing important anecdotes, not even a scrap of paper for scribbling “Hall Bed 9” as a reminder of where you’re located.

“Hall Bed.” Let’s pause and discuss the “Hall Bed.” A cute way to assure a patient they’re being escorted to a bed that is, in fact, nothing more than a chair set on one side of the hall between the wall and a flimsy cubicle divider. No curtain. No privacy. A thin—unwarmed—blanket provided upon request. But no visitors permitted because…well, it’s already nothing more than a chair. No room for any other chairs. But you’re a grown-ass adult. What do you need a visitor for? Why would you need your caregiver with you for support and reassurance and to speak up while you huddle on your hall bed in severe pain for hours as no one talks to you? (My bad—it did recline. Hence the “bed” part)

Moving on.

Perhaps doctors are like waiters; so accomplished they can remember complex medical histories and current complaints without resorting to notes despite an overwhelming patient load. Or there’s that repetitive record that is, of course, always accurate and never wrong and never keeps an entire list of every prescription you’ve been on since your day of birth. That chart everyone reads so faithfully, which is why you never have to take urine pregnancy tests despite the fact you had a hysterectomy in 2017.

Or have to repeat—three times—you’re positive the pain isn’t menstrual in origin as you no longer have any reproductive organs.

Medical records are infallible. And you fill them out at every single visit to prevent silly accidents or misinformation. They’re your lifeline in a hospital setting. Without those bits of data floating from one station to the next, you could end up with a doctor panicking that you have a strange foreign body instead of hemaclips from your appendix removal (true story). Or a technician commenting they can’t locate your gallbladder when it was clearly removed in 2003 (also a true story—though to be fair, a doctor sent the request for the images).

Why else would you constantly update everything you can in the THREE MyChart apps on your phone? (None of which talk to each other because that would be madness) And grit your teeth as you fill out every form at every pre-visit and again at every visit.

Because you know those doctors must be relying on your records to do their jobs. Out of your sight, they’re scrolling through the pages and pages of medical history, hunting for answers and clues. You trust there’s a reason you constantly confirm and update the same information every time you turn around.

Why else would medical professionals disappear for hours on end?

Medical records don’t exist for patients. We may get pressed into updating the more mundane aspects of their information—the boring details no one will ever pay attention to, such as identity, family health background, and current mental state—but we’re nothing more than outside observers of a giant experiment. The medical details are going into a giant data pool searching for the answer to a single question:

Who is sick enough?

Think about it. What is triage but a Jenga game of determining where the weakest log lies? Who is sick, and who is faking? And out of the pool of those deigned “sick,” which are sick enough to mandate care and concern? Shift the truly ill to the top of the stack and leave the rest at the bottom—forgotten until there’s nothing interesting to play with.

Or until the tower falls.

Doctors slip away to comb through records for signs of red. Are there flashing words drawing them like flies to a bug zapper? Do warnings pop up as promises of more work and better interaction? Those are the patients they want to devote their time to. (And now they’re getting AI programs to do the scanning for them, saving them reading time) They don’t want to spend time with people who have histories with words like “chronic pain,” or “recommended psych evaluation,” or “seven ER visits in four months.” Such phrases serve as a different red flag; one that says, “This person is not sick enough.”

Do you have something verging on severe? Are you in imminent danger of dying? Will you bring excitement to the department and keep everyone hovering over your vital signs from moment to moment?

No?

Then you are not sick enough.

How you feel about the situation is immaterial.

Maybe you can’t stand upright. You might have vomited even the empty contents of your stomach (an impressive feat, let me tell you). You may be in so much pain you can’t stop shaking and have retreated inside, so it takes multiple attempts for people to get a response from you. And you may have lab work and scans that scream ABNORMAL.

But you’re not sick enough to make the cut.

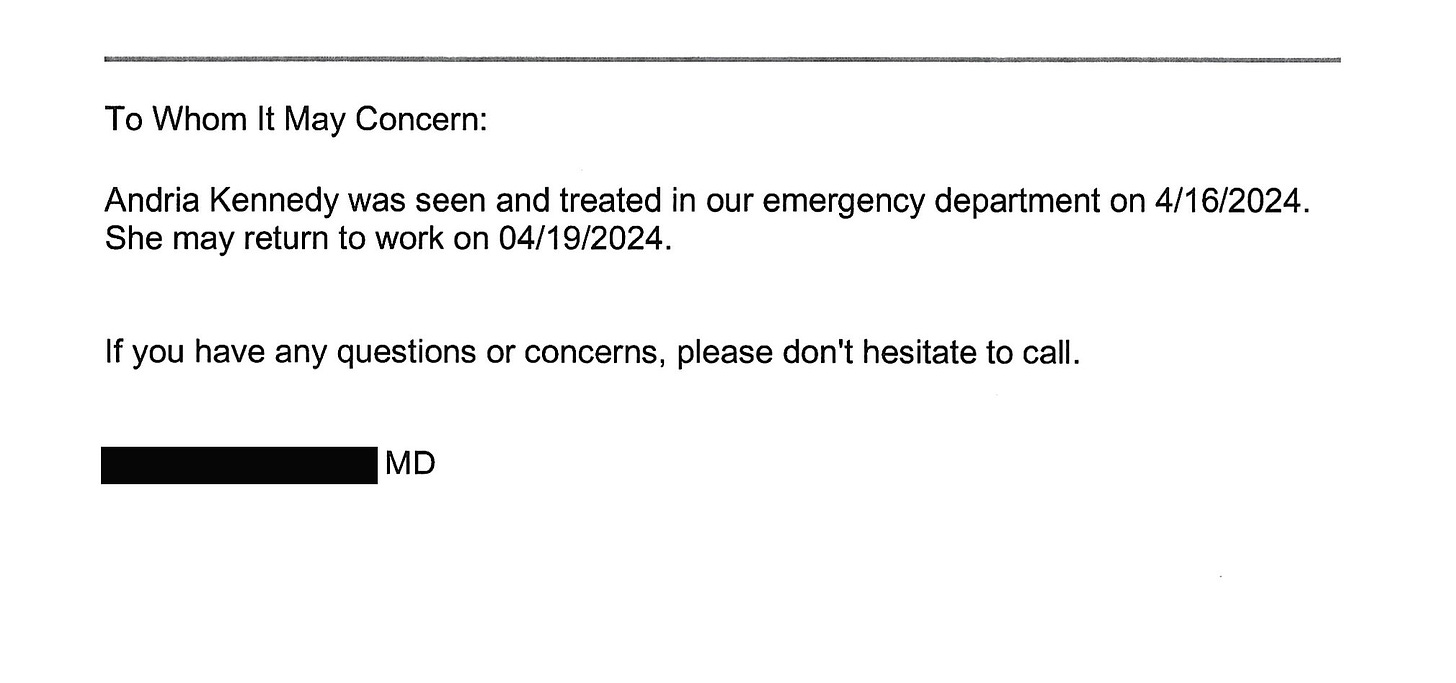

So you will sit and wait with the other people judged “not sick enough.” And, in the end, you’ll be awarded the highest honor your medical records allow: A sick note.

Ahem, a “sick” note.

The medical team will at least acknowledge they saw you and provided some level of treatment. No one is going to go crazy and admit you were sick and might need any kind of sympathy.

Not with your medical records.